Introduction

Here’s something they don’t teach in engineering school: designing equipment that works perfectly in your lab doesn’t mean it’ll pass IECEx certification testing. I learned this the hard way while consulting for a manufacturer whose “explosion-proof” motor controller failed testing spectacularly—not because the design was unsafe, but because the engineers didn’t understand the specific requirements of Ex d protection. They spent six months redesigning what could’ve been correct initially if they’d known what certification actually demands.

Designing explosion-proof equipment for IECEx certification isn’t about making things generally robust; it’s about satisfying precise technical requirements that vary by protection type, equipment group, temperature class, and installation zone. This guide takes you through the engineering principles, design decisions, and testing requirements that separate equipment that achieves first-time certification from equipment that cycles through expensive re-design loops. Whether you’re developing enclosures, instruments, or complex control systems for UAE, Saudi Arabia, or global hazardous area markets, understanding these principles upfront saves enormous time and money.

Types of Protection (Ex d, e, i)

IECEx recognizes multiple protection types, each preventing ignition through different physical principles. Choosing the wrong protection type for your equipment is the fastest route to certification failure. Let’s break down the three most common types manufacturers encounter.

Ex d: Flameproof Enclosures

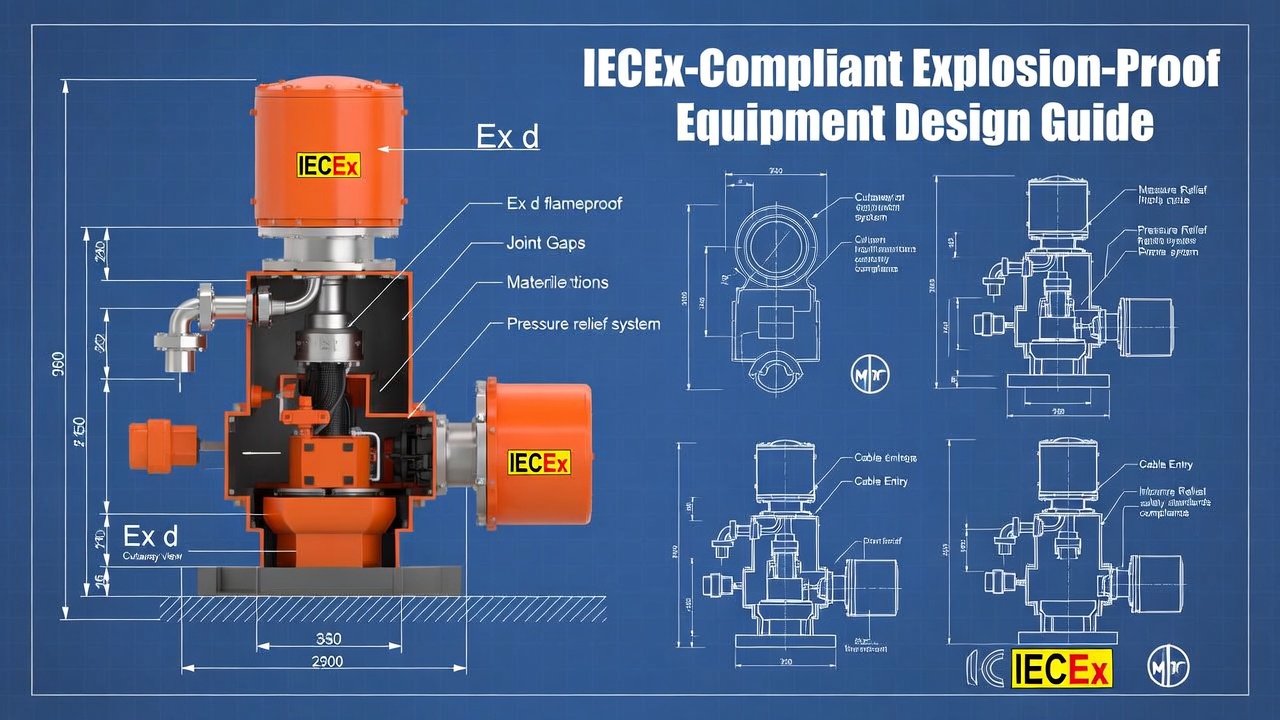

Ex d protection contains any explosion that occurs inside the enclosure and prevents it from igniting the external atmosphere. Think of it as controlled containment—if something sparks or arcs inside, the enclosure withstands the explosion pressure and cools the gases before they escape through designed gaps. This protection type suits equipment with arcing components: motor starters, switches, circuit breakers, and relay panels.

The engineering requirements get specific. Your enclosure must withstand reference pressure for the gas group you’re targeting—IIA, IIB, or IIC. Group IIC (hydrogen, acetylene) demands the highest strength because these gases produce maximum explosion pressure. The enclosure joints need precisely controlled gaps—too wide and flame passes through; too narrow and thermal expansion causes binding. We’re talking tolerances measured in tenths of millimeters maintained across wide temperature ranges.

Fastener requirements matter enormously in Ex d design. Those bolts holding your cover? They need specific quantity, size, and spacing calculations. Thread engagement must be verified. Some manufacturers use captive screws to prevent installation with wrong bolt length—smart thinking that prevents field failures. The temptation to use standard industrial enclosures and call them explosion-proof? That’s how certification attempts fail.

Ex e: Increased Safety

Ex e takes a different approach: prevent ignition sources from occurring rather than containing explosions. This protection type applies additional safety measures to equipment that doesn’t normally produce arcs or hot surfaces. Terminal boxes, junction boxes, squirrel-cage motors, and luminaires commonly use Ex e protection.

The design philosophy emphasizes prevention through redundancy. Electrical connections require higher creepage and clearance distances than standard equipment—we’re preventing tracking and flashover. Terminal blocks need specific clamping force to prevent loose connections that create resistance heating. Insulation requirements exceed standard ratings significantly. Temperature rise must stay well below ignition temperatures with generous safety margins.

What surprises many engineers? Ex e equipment requires type testing that includes overload scenarios. Your motor might run perfectly at rated current, but certification testing runs it at 1.5x rated current to verify it doesn’t reach dangerous temperatures. Design margins matter—if you’re operating near limits at normal conditions, you’ll fail certification testing. Understanding comprehensive IECEx zones and protection concepts helps match the right protection type to your application.

Ex i: Intrinsic Safety

Ex i represents the most elegant solution—limit available energy so that even worst-case faults can’t generate sufficient heat or sparking to cause ignition. This protection type dominates instrumentation: sensors, transmitters, analyzers, and field devices operating in harsh or inaccessible locations.

The engineering challenge? Every component’s energy storage must be calculated and proven safe through fault analysis. Capacitors store energy that could spark during disconnection. Inductors store energy that releases during interruption. Your calculations must prove that under any conceivable fault condition—short circuits, open circuits, component failures, even earth faults—the energy released remains below the minimum ignition energy of the target gas.

Ex i design demands partnership with the hazardous area. Field devices (Ex i) connect to associated apparatus (barriers, isolators) located in safe areas. The system safety depends on both components plus the cable connecting them. Cable capacitance and inductance affect safety calculations. This interconnection complexity makes Ex i systems challenging but incredibly safe when properly designed. Many engineers pursue specialized IECEx certification training to master intrinsic safety calculations thoroughly.

There are other protection types—Ex p (pressurization), Ex m (encapsulation), Ex o (oil immersion)—each with specific applications. The key is matching protection type to your equipment’s ignition risk and operational requirements. A common mistake? Choosing Ex d for everything because it seems straightforward. Often, Ex e or Ex i provides simpler, more cost-effective solutions if your equipment’s characteristics suit those protection types.

Material & Component Selection

Materials matter more in explosion-proof design than typical electrical equipment. You’re not just selecting for mechanical strength and electrical properties—you’re choosing materials that maintain safety characteristics across temperature extremes, chemical exposures, and mechanical stresses unique to hazardous environments.

Start with enclosure materials. Aluminum alloys are popular for Ex d enclosures due to favorable strength-to-weight ratios and corrosion resistance. However, aluminum has a critical weakness: it’s a non-sparking metal that’s actually safer than steel in some scenarios, but certain aluminum alloys contain magnesium content that could react with specific chemicals. IECEx standards limit magnesium content to prevent this risk. Your material certificates must prove compliance—generic aluminum won’t suffice.

Stainless steel offers excellent corrosion resistance for marine and chemical plant environments. But not all stainless grades meet requirements—austenitic grades (304, 316) are generally acceptable; ferritic grades might create issues in specific applications due to magnetic properties affecting certain devices. Material traceability becomes critical during certification audits. That cheap steel you sourced without documentation? It’s a certification roadblock waiting to happen.

Plastic and polymer materials require careful selection. Many modern enclosures use polycarbonate, polyester, or fiber-reinforced polymers for weight reduction and corrosion immunity. These materials must prove they don’t generate hazardous static charges, maintain impact resistance across their temperature range, and resist degradation from UV exposure or chemicals. Antistatic additives, UV stabilizers, and impact modifiers all require documentation in your technical file.

Gaskets and seals deserve special attention. That rubber O-ring might work fine in your office environment but chemical plants expose seals to hydrocarbon vapors, cleaning solvents, and temperature cycling. Your gasket material must maintain compression set resistance, chemical compatibility, and temperature stability throughout the equipment’s rated operating range. Silicone, Viton, EPDM—each has specific applications and limitations. Documentation must prove your selection is appropriate. For regional applications, proper IECEx certification in UAE requires understanding local environmental conditions affecting material selection.

Component selection gets even more critical. Every electrical component inside certified equipment must have documented ratings and characteristics. That relay you’re using? You need data sheets proving its contact rating, insulation voltage, temperature rise, and breaking capacity. Certification bodies will request this documentation, and “I bought it from a distributor” isn’t sufficient answer.

Here’s where many designs fail: component substitutions. Your prototype might use premium components, but production cost pressures lead to substituting cheaper alternatives. Unless those substitutes have equivalent specifications and documentation, you’ve invalidated your certification. The IECEx ExQA system specifically monitors component control to prevent this problem. Build component traceability into your procurement process from the start.

PCB materials matter for Ex e and Ex i equipment. Standard FR4 laminate might not meet creepage and clearance requirements when tracking resistance is considered. Certification bodies examine PCB specifications, copper weight, solder mask properties, and conformal coating characteristics. Your PCB fabricator needs clear specifications and must maintain consistent quality—another reason ExQA certification proves valuable.

Testing Requirements

Here’s where design meets reality. IECEx certification isn’t granted based on calculations alone—your equipment must survive rigorous physical testing at accredited laboratories. Understanding these tests during design phase helps you build equipment that passes first time.

Type Testing

Every protection type has specific test requirements defined in IEC 60079 standards. For Ex d enclosures, expect explosion testing where the chamber is filled with explosive gas mixture, ignited, and the enclosure must contain the explosion without flame transmission. This test repeats multiple times with different orientations and ignition sources. Your enclosure either contains the explosions or fails spectacularly—there’s no partial credit.

Impact testing verifies enclosures withstand mechanical abuse. Test equipment drops specified hammers from calculated heights onto your enclosure. Plastic enclosures often struggle with low-temperature impact tests—materials that seem tough at room temperature become brittle at -40°C. Design with these extremes in mind, or your test failures will be expensive.

Thermal cycling proves your equipment maintains safety across rated temperature range. Tests cycle equipment between temperature extremes while monitoring critical parameters. Gaskets that seal perfectly at 20°C might leak at -20°C or 60°C. Expansion coefficients of dissimilar materials create problems—your aluminum enclosure expands differently than steel fasteners, potentially affecting joint gaps critical to flameproof integrity.

Ingress protection (IP rating) testing verifies environmental sealing. Most hazardous area equipment requires minimum IP65 (dust-tight, water-jet resistant) or IP66 (powerful water jets). Testing involves actual dust exposure in controlled chambers and water spray from specified angles and pressures. Gasket design, cable entry sealing, and cover interface all get exposed to real-world stress.

Ex i Testing

Intrinsic safety testing takes different approach. Since the protection relies on energy limitation, testing verifies your calculations through fault condition testing. Every conceivable fault gets induced—short circuits, open circuits, component failures—while spark generation equipment monitors whether sufficient energy exists to ignite test gases. These tests run hundreds of cycles to prove statistical safety.

Temperature rise testing under fault conditions verifies that even with maximum fault current, component temperatures stay below ignition points. Your calculations might say it’s safe, but only testing proves it. This is why component specifications and safety factors matter—real-world variations from nominal specifications can’t compromise safety.

EMC Testing

Don’t forget electromagnetic compatibility testing. While not strictly part of explosion protection, most industrial equipment requires EMC compliance. EMC issues can compromise intrinsic safety by inducing unexpected currents or voltages. Design with EMC in mind from the start—retrofitting filtering and shielding after initial design multiplies costs significantly. Resources comparing IECEx vs ATEX requirements highlight how both systems address EMC in certified equipment design.

Avoiding Certification Delays

Time is money in product development, and certification delays directly impact market entry. Based on reviewing hundreds of certification applications, certain strategies consistently reduce timeline.

Early Engagement

Don’t wait until design completion to contact certification bodies. Engage during concept phase. Most certification bodies offer pre-assessment services where they review preliminary designs and flag potential issues. This early feedback prevents designing yourself into corners that require major revisions later. Cost for pre-assessment? Often $2,000-$5,000. Value when it prevents a $50,000 redesign? Priceless.

Documentation Discipline

Complete technical documentation is the single biggest factor in certification speed. Certification bodies review design drawings, calculations, component specifications, test procedures, quality manuals, and manufacturing instructions. Incomplete documentation causes immediate delays while you scramble to produce missing information. Create a documentation checklist early and track completion religiously.

Your technical file should include assembly drawings with part numbers, individual component drawings, electrical schematics, wiring diagrams, PCB layouts, bill of materials with component specifications, safety calculations (especially for Ex i), temperature rise calculations, fault analysis, material certificates, component data sheets, test procedures, quality control procedures, and manufacturing work instructions. If that list seems excessive, remember: incomplete documentation is the number one cause of certification delays.

Component Pre-Approval

For Ex i designs especially, consider using pre-approved components. Many component manufacturers publish IECEx evaluation data—capacitors, inductors, diodes with certified maximum values. Using these pre-approved components simplifies your safety calculations and reduces certification body’s assessment time. Custom components require extensive testing and documentation.

Realistic Schedules

Plan 6-12 months minimum from application to certificate issuance. This assumes complete documentation and first-time test success. Factor buffer time for inevitable questions, document revisions, and potential retest if issues emerge. Marketing teams hate hearing “12 months,” but setting unrealistic expectations causes worse problems when you miss them. Understanding the complete IECEx certification process helps establish achievable timelines.

Test Laboratory Coordination

Accredited test laboratories book months in advance, especially for specialized explosion testing. Book testing slots early, even before documentation review completes. Most labs allow rescheduling with notice. Missing test slots can delay certification by months while waiting for next availability. Also, prepare multiple samples—testing is destructive, and you’ll need spares if initial samples fail.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Ex d?

Ex d stands for “flameproof enclosure” protection type—one of the most widely used explosion protection methods in IECEx certification. The “Ex” designation indicates equipment for explosive atmospheres, while “d” specifically denotes the flameproof protection concept. Ex d works by containing any explosion that occurs inside the enclosure and preventing it from igniting the surrounding hazardous atmosphere. When electrical equipment sparks or arcs—common with switches, relays, and motor starters—the enclosure withstands the internal explosion pressure and cools the hot gases before they escape through precisely engineered joints and gaps. This cooling effect prevents external ignition even though combustion occurred inside. Ex d enclosures require robust mechanical construction with controlled joint gaps (usually 0.1-0.4mm depending on gas group), sufficient wall thickness to withstand explosion pressure, and specific fastener requirements to maintain integrity. The protection type suits equipment with unavoidable ignition sources operating in Zone 1 or Zone 2 classified areas. Common Ex d applications include motor starters, switchgear, control panels, junction boxes with terminals, and lighting fixtures with potential arcing components. Design standards specify minimum requirements for enclosure strength, joint dimensions, fastener specifications, cable entry sealing, and material selection. Testing involves actual explosion tests where the enclosure contains ignited explosive gas mixtures without flame transmission—dramatic testing that either validates design or reveals fatal flaws immediately.

How to select components for IECEx compliance?

Component selection for IECEx-compliant equipment demands systematic approach balancing technical requirements, documentation availability, and supply chain reliability. Start by understanding your protection type’s specific requirements—Ex d, Ex e, and Ex i each impose different constraints on components. For Ex i designs, every component’s energy storage characteristics (capacitance, inductance) matter because they affect safety calculations. Select components with published parameters and generous margins below calculated limits. Many manufacturers publish IECEx evaluation data for their components, dramatically simplifying certification—using pre-evaluated capacitors, inductors, and semiconductors reduces assessment time significantly. For Ex d and Ex e protection, focus on components with adequate voltage ratings, temperature ratings, and mechanical robustness. Certification bodies require complete component data sheets proving specifications, so select components from reputable manufacturers who provide comprehensive technical documentation. Avoid obscure or counterfeit components lacking proper documentation. Consider component availability and lifecycle—selecting obsolete components creates problems when you need replacements during production. Build approved component lists and control substitutions rigorously through your quality system. For critical components like relays, contactors, and terminal blocks, verify their suitability for hazardous area application—some components generate excessive heat or sparking unsuitable for explosion protection. Material compatibility matters for components exposed to process chemicals—elastomers, plastics, and metals must resist degradation in your target environment. Temperature ratings must cover your equipment’s operating range plus safety margins for fault conditions. For connectors and cable glands, select components with their own IECEx or ATEX certification when possible—using certified components simplifies system certification. Document every component selection decision with technical justification—certification audits will question component choices, and “it was cheapest” isn’t acceptable answer. Professional training through programs like IECEx certification courses helps engineers develop systematic component selection skills. For regional markets, understanding requirements through resources like certification comparisons for UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar provides valuable context for component decisions affecting multiple markets.

Conclusion

Designing explosion-proof equipment that achieves IECEx certification requires more than general engineering competence—it demands specific knowledge of protection types, rigorous material selection, comprehensive testing understanding, and disciplined documentation practices. The engineers who succeed approach certification as an integral design requirement from concept phase, not an afterthought bolted onto completed designs. They select appropriate protection types matching equipment characteristics, choose components with certification in mind, design with testing requirements understood, and maintain documentation discipline throughout development.

Your investment in proper design methodology pays immediate dividends: first-time certification success, reduced testing costs, faster market entry, and equipment reliability that builds lasting reputation. The alternative—learning through expensive test failures and certification rejections—costs far more than initial investment in knowledge and planning. Start your next explosion-proof design by engaging certification bodies early, studying relevant IEC standards thoroughly, and building systematic design processes that embed certification requirements into every decision. The Middle Eastern markets demand this excellence, and your commercial success depends on delivering it consistently.